Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

“We think you’re crazy!” “Wow, we’d never try that!” “What are you going to do if you get stranded?”

Almost every time we broached the idea of driving our 2019 Kona EV across Canada, we got these responses in return. Except once. “You’re really worried about climate change, and you want to do something about it, right?” said my brother. “So if you decide to drive your gas car to visit us, what message does that give? Go for it!”

So we did. On May 28, we (my wife, our poodle, and I) boarded the early ferry from our home on Vancouver Island, BC, and drove to spend time with family in southern Ontario. In US terms, that’s equivalent to leaving San Juan Island, Washington, and going to see family in New York. And after 56 days and 10,358 kilometres (6,436 miles), I’ve learned quite a bit about long-distance EV travel.

For the purposes of this article, it’s important for American readers to understand two things about Canada. Both countries are big, but unlike traveling across the States, Canada has huge expanses of, well, nothing except wilderness — no towns, no accommodation, no restaurants, just the occasional gas station. Second, there is a lot of political division from one province to the next. Some have quite progressive provincial governments, like our province of British Columbia or Quebec, which recognize that climate change is real and have implemented policies to mitigate it. Others like Alberta believe that the entire economy is linked to oil and gas, and therefore tend to be less sympathetic towards solutions like electric vehicles. Finally, there are provinces like Ontario, simply conservative by nature, where financial incentives to create social change are viewed with suspicion, regardless of how important those changes may be.

Why are these political differences important here? Because infrastructure like public charging stations needs to be ahead of the demand curve. Why would anyone consider purchasing an electric vehicle if there are no places to charge it beyond their home? And why would any for-profit corporation go to the expense of installing and maintaining public charging stations if there were few if any electric vehicles to use them? EVs (along with electric heat pumps and rooftop solar) might be a great climate solution, but what’s the chicken and what’s the egg? Voters determine that by choosing what kind of government they want in power.

With these facts in mind, here are the main takeaways from our nearly two month trip across three time zones:

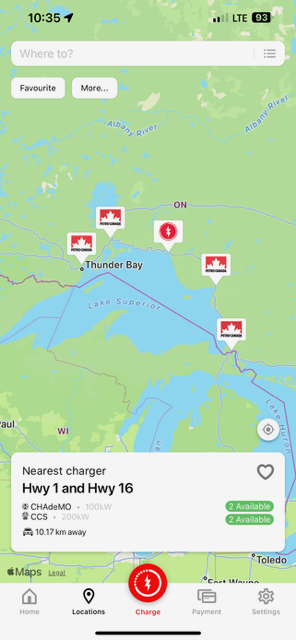

- With a few exceptions detailed below, level 3 fast charging stations were readily available all the way, and only once did we have to wait for another vehicle to finish charging. One exception was in a major city where someone is going around cutting the cables — probably for the value of the copper wire. By the time I found a charger that was working, we were down below 50 km of range (a level that would put my wife into heart attack mode, but luckily she wasn’t in the car at the time). Another exception was in a small Ontario town where the entire station had been removed, but still showed on the app.

- Then come the ones that are supposed to be working, but when you get there, are not. Range anxiety comes from situations where you simply don’t know. Maybe the territory is new, you haven’t experienced it, and you are counting on and trusting the information available to you on your phone. Or maybe you’ve used the station before and are counting on it again. In our case, where much of our return trip was on the same road as our eastbound portion, we knew where the stations were located and had used them only a few weeks earlier. Twice on our return trip we arrived and discovered that no stations were working, and the result ranged from panic to significant disruption of plans. Luckily, with some research, level 2 stations were available, but the time delay was rather inconvenient.

- Some stations charge by the hour, others by kWh consumed. Older vehicles like ours cannot accept charge greater than 70–75 kW, so we are penalized at hourly stations with capacities up to 350 kW.

- The cost of power for EVs varies widely across the country and seems not to bear a relationship to residential electricity rates. For example, British Columbia and Ontario have roughly similar residential electricity rates, at about $0.12/kWh. BC level 3 stations sell power between $0.34.8 and $0.39/kWh, or at about three times the residential rate. (Some still sell by the hour, but at a 50 kW station, the cost per kWh is about the same). Ontario is a different story. If sold by power used, the cost there is $0.62/kWh, about five times the residential rate. The hourly rate is $30 at 100 kW stations, competitive to BC if your vehicle can absorb that level of charge, but punitive for those of us who cannot. For us, the cost of charging in Ontario was nearly double that in British Columbia.

The bottom line is that with enough time, planning and patience, a lengthy cross-country trip by EV is not only possible, but is also fun and rewarding. We all need bathroom, lunch, and coffee breaks, and the dog has his own set of reasons to stop. With a bit of advance planning, most if not all stops to charge can be tied into other activities — sometimes to the place where we wished we had longer to charge, not chomping at the bit to get going. On unfamiliar roads, our rule was to never pass up a charging station. This meant that we were stopping every couple of hours, but it avoided the risk of the one we really needed being either in use or inoperative.

Having said that, the EV infrastructure has a long way to go if range anxiety is to be eliminated. I had to download 10 apps on my phone, either to find or to activate charging stations. No single app showed all the stations, let alone provided a way to activate the stations or pay for the power used. On top of that, unless I was willing to scroll across the map, discovering stations along the way, I had to enter the name of a town or city to find them. The problem is that the ones we really needed were often nowhere close to any population centre at all — certainly no population centre that I ever knew existed. It would have been much more convenient to simply enter the highway number we planned to travel that day, and have it show every level 2 and level 3 charger within × kilometres of that route. I did find Google Maps to be of some help in this regard, but considering the distances involved compared to the size of the phone screen, they were easy to miss even if they did show up at higher zooms.

In one province, but one province only, many Tesla stations were required to include at least one CCS and CHAdeMO unit. We found these stations to be extremely helpful, mainly because of the sheer number of Tesla stations there are, and how they fill in locations not adequately served by other providers. The problem is that on a national level, Tesla stations don’t have CCS plugs to fit our Kona. There they are, six bright red and white chargers all in a row, and they’re totally useless to the rest of us. That has to change.

Finally, there is an imperative for stations to be monitored and maintained so that they are operative 100% of the time. There are too many locations across the country where a single charger or pair of chargers is the only option — absolutely critical, not only to the journey, but also to the comfort and safety of the people involved. It’s one thing to search for and then drive to a Level 2 charger a few kilometres away and be forced to wait up to four hours to get a sufficient charge. But it’s another much scarier scenario to find that charger in the middle of nowhere inoperative, but then with no alternative for charging, no accommodation to stay in, no restaurant for a meal, and no easy way to get help. There aren’t many of these across Canada, and fortunately for us, they were working. But like airplanes, 99% isn’t good enough. It’s got to be 100% or another airplane close by could cause a disaster.

So, would we do it again? You bet we would! Awesome scenery, wonderful people, great food, and lots of adventure. There’s also the satisfaction of travelling without all those emissions contributing to the climate crisis. But here’s the best news that I’ve saved to the end. Our total electricity charging cost was C$757.68. The gas mileage on an ICE Kona is rated at 31 miles/US gallon, or 7.6 litres/100 km. At an average price across the country of C$1.56/litre, it’s an easy calculation to show that if we had driven a gas Kona, our cost would have been C$1,228. For bragging rights and nearly $500 in my pocket, I’d do this every time.

By John Laing

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

Read the full article here